A reporter eyes French designer Gael Langevin's multilingual InMoov robot,

unveiled in May. Legions of robots carry out our instructions unreflectively,

but how do we ensure that they always work in our best interests? Vadim

Ghirda

by Simon Parkin

More than 400 years ago, according to legend, a rabbi knelt by the banks of

the Vltava River in what is now the Czech Republic. He pulled handfuls of clay

out of the water and carefully patted them into the shape of a man.

The Jews of Prague, falsely accused of using the blood of Christians in

their rituals, were under attack. The rabbi, Judah Loew ben Bezalel, decided

that his community needed a protector stronger than any human. He inscribed the

Hebrew word for "truth", emet, onto his creation's forehead and placed a capsule

inscribed with a Kabbalistic formula into its mouth. The creature sprang to

life.

This Golem patrolled the ghetto, protecting its citizens and carrying out

useful jobs: sweeping the streets, conveying water and splitting firewood. All

was harmonious until the day the rabbi forgot to disable the Golem for the

Sabbath, as he was required to, and the creature embarked on a murderous

rampage. The rabbi was forced to scrub the initial letter from the word on the

Golem's forehead to make met, the Hebrew word for "death". Life slipped from the

Golem and he crumbled into dust.

This cautionary tale about the risks of building a mechanical servant in

man's image has gained fresh resonance in the age of artificial intelligence.

Legions of robots carry out our instructions unreflectively. How do we ensure

that these creatures, regardless of whether they're built from clay or silicon,

always work in our best interests? Should we teach them to think for themselves?

And if so, how are we to teach them right from wrong?

In the 1956 film Forbidden Planet, Robby the Robot makes its screen debut,

the first of many appearances. It is multiskilled and incapable of harming

humans. Archive Photos

In 2017, this is an urgent question. Self-driving cars have clocked up

millions of kilometres on our roads while making autonomous decisions that might

affect the safety of other human road-users. Roboticists in Japan, Europe and

the United States are developing service robots to provide care for the elderly

and disabled. One such robot carer, which was launched in 2015 and dubbed Robear

(it sports the face of a polar-bear cub), is strong enough to lift frail

patients from their beds; if it can do that, it can also, conceivably, crush

them. Since 2000 the US Army has deployed thousands of robots equipped with

machineguns, each one able to locate targets and aim at them without the need

for human involvement (they are not, however, permitted to pull the trigger

unsupervised).

Sense of dread

Public figures have also stoked the sense of dread surrounding the idea of

autonomous machines. Elon Musk, the tech entrepreneur, claimed that artificial

intelligence was the greatest existential threat to mankind. Last northern

summer the White House commissioned four workshops for experts to discuss this

moral dimension to robotics. As Rosalind Picard, director of the Affective

Computing Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology puts it: "The

greater the freedom of a machine, the more it will need moral standards."

In a futuristic office complex on the meandering Vltava River, near where

the rabbi sculpted his Golem, an orderly bank of computers hums. They make for

unlikely teachers, but they are as dedicated as any human to the noble task of

education. Their students don't sit in front of each computer's screen, but

rather on their hard drives.

This virtual school, which goes by the name of GoodAI, specialises in

educating artificial intelligences (AIs): teaching them to think, reason and

act. GoodAI's overarching vision is to train artificial intelligences in the art

of ethics. "This does not mean pre-programming AI to follow a prescribed set of

rules where we tell them what to do and what not to do in every possible

situation," says Marek Rosa, a successful Slovak video-game designer and

GoodAI's founder, who has invested $US10 million in the company. "Rather, the

idea is to train them to apply their knowledge to situations they've never

previously encountered."

The Golum was useful to the Jews of Prague until its programming was

neglected and it turned murderous. Lonely Planet

Experts agree that Rosa's approach is sensible. "Trying to pre-program

every situation an ethical machine may encounter is not trivial," explains Gary

Marcus, a cognitive scientist at New York University and chief executive officer

and founder of Geometric Intelligence. "How, for example, do you program in a

notion like 'fairness' or 'harm'?"

Neither, he points out, does this hard-coding approach account for shifts

in beliefs and attitudes. "Imagine if the US founders had frozen their values,

allowing slavery, fewer rights for women, and so forth? Ultimately, we want a

machine able to learn for itself."

Blank slate

Rosa views AI as a child, a blank slate onto which basic values can be

inscribed, and which will, in time, be able to apply those principles in

unforeseen scenarios. The logic is sound. Humans acquire an intuitive sense of

what's ethically acceptable by watching how others behave (albeit with the

danger that we may learn bad behaviour when presented with the wrong role

models).

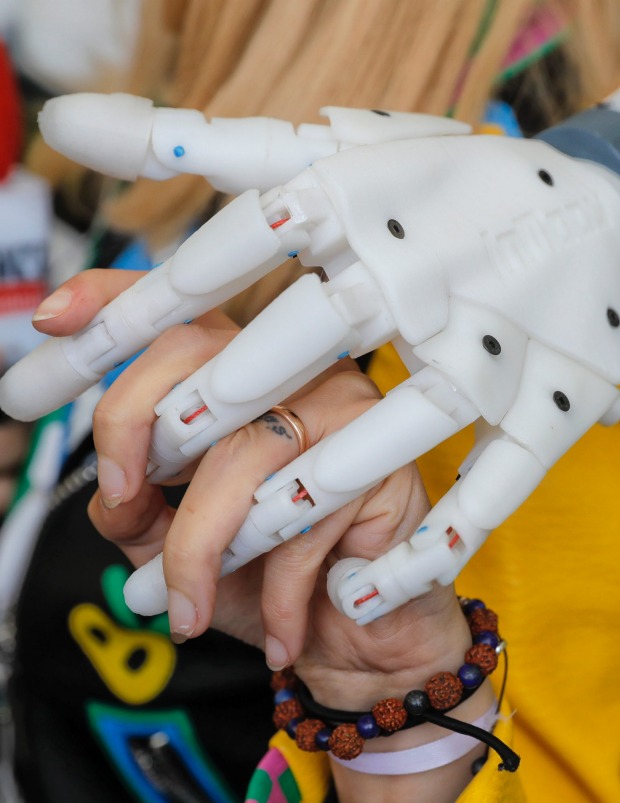

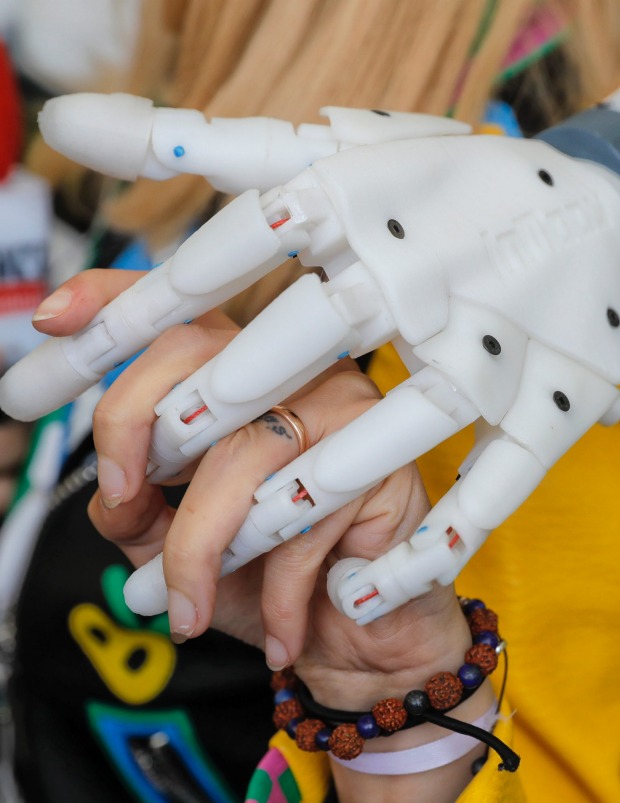

A member of the public admires Gael Langevin's InMoov robot, which is based

on the first prosthetic hand made on a 3D printer. Vadim Ghirda

GoodAI polices the acquisition of values by providing a digital mentor, and

then slowly ramps up the complexity of situations in which the AI must make

decisions. Parents don't just let their children wander into a road, Rosa

argues. Instead they introduce them to traffic slowly. "In the same way we

expose the AI to increasingly complex environments where it can build upon

previously learnt knowledge and receive feedback from our team."

GoodAI is just one of a number of institutions dedicated to understanding

the ethical dimension of robotics that have sprung up across the world in recent

years. Many of these bodies enjoy grand, foreboding titles: The Future of Life

Institute, The Responsible Robotics Group and The Global Initiative on Ethical

Autonomous Systems. There is a number of competing ideas in circulation about

how best to teach morality to machines. Rosa champions one, Ron Arkin

another.

Arkin is a balding roboethicist in his mid-60s, with eyes that droop under

panoramic spectacles. He teaches computer ethics at Georgia Tech in sweltering

Atlanta, but his work is not confined to the classroom.

Arkin's research has been funded by a range of sources, including the US

Army and the Office of Naval Research. In 2006, he received funding to develop

hardware and software that will make robotic fighting machines capable of

following ethical standards of warfare. He has argued that robot soldiers can be

ethically superior to humans. After all, they cannot rape, pillage or burn down

a village in anger.

Roboticists in Japan, Europe and the United States are developing service

robots to provide care for the elderly and disabled. But are robot lawyers

possible? Posteriori

Teaching robots how to behave on the battlefield may seem straightforward,

since nations create rules of engagement by following internationally agreed

laws. But not every potential scenario on the battlefield can be foreseen by an

engineer, just as not every ethically ambiguous situation is covered by, say,

the Ten Commandments.

Tactical v moral decisions

Should a robot, for example, fire on a house in which a high-value target

is breaking bread with civilians? Should it provide support to a group of five

low-ranking recruits on one side of a besieged town, or one high-ranking officer

on the other? Should the decision be made on a tactical or moral basis?

To help robots and their creators navigate such questions on the

battlefield, Arkin has been working on a model that differs from that of GoodAI.

The "ethical adapter", as it's known, seeks to simulate human emotions, rather

than emulate human behaviour, in order to help robots to learn from their

mistakes. His system allows a robot to experience something similar to human

guilt.

Robotic arms work on car production for Suzuki. Self-driving cars have

clocked up millions of kilometres on our roads while making autonomous decisions

that might affect the safety of human road-users. Akos Stiller

"Guilt is a mechanism that discourages us from repeating a particular

behaviour," he explains. It is, therefore, a useful learning tool, not only in

humans, but also in robots.

"Imagine an agent is in the field and conducts a battle damage assessment

both before and after firing a weapon," Arkin says. "If the battle damage has

been exceeded by a significant proportion, the agent experiences something

analogous to guilt."

The sense of guilt increases each time, for example, there's more

collateral damage than was expected. "At a certain threshold the agent will stop

using a particular weapon system. Then, beyond that, it will stop using weapons

systems altogether," he adds. While the guilt that a robot might feel is

simulated, the models are nevertheless taken from nature and, much like in

humans, have a tripartite structure: a belief that a norm has been violated, a

concern about one's actions, and a desire to return to a former state.

It's an ingenious solution but not one without issues. For one, the guilt

model requires things to go wrong before the robot is able to modify its

behaviour. That might be acceptable in the chaos of battle, where collateral

damage is not entirely unexpected. But in civilian homes and hospitals, or on

the roads, the public's tolerance for deadly robotic mistakes is far lower. A

killer robot is more likely to be disassembled than offered the chance to learn

from its mistakes.

Inspiration in the library

From virtual classrooms to simulated guilt, the approaches to teaching

robot morality are varied, embryonic and, in each case, accompanied by distinct

problems. At Georgia Tech, Mark Riedl, the director of the Entertainment

Intelligence Lab, is trying out a method that finds its inspiration not in the

classroom but in the library.

By reading thousands of stories to AIs, and allowing them to draw up a set

of rules for behaviour based on what they find, Riedl believes that we can begin

to teach robots how to behave in a range of scenarios from a candlelit dinner to

a bank robbery. A range of organisations and companies, including DARPA, the US

Department of Defence's R&D agency, the US Army, Google and Disney, funds

the team's work.

When we meet for a burger in a restaurant close to his laboratory, Riedl

agrees with GoodAI's basic philosophy. "It's true: the answer to all of this is

to raise robots as children," he says. "But I don't have 20 years to raise a

robot. That's a very time-consuming and expensive process. Just raising one kid

is all I can handle. My idea was to use stories as a way of short-circuiting

this learning process."

French designer Gael Langevin unveils his InMoov robot at a technology fair

in Bucharest. As technologies commingle and are administered by AIs, the danger

is our technological progress has outpaced our moral preparedness. Vadim

Ghirda

Riedl arrived at this idea while researching how stories might be used to

teach AIs the rules of human social situations. "If Superman dresses up as Clark

Kent and meets someone for dinner, you have this nice little demonstration of

what people do when they go into a restaurant," says Riedl. "They get a seat.

They order their drinks before their food. These are social values, in terms of

the order of things that we like to do things in. Now, there's usually no

ethical dilemma in terms of restaurants. But there are cues, such as: 'Why

didn't they go in the kitchen and get the food?' I couldn't really tell an AI

why not, but I can show it that's not what you're supposed to do."

Riedl crowd-sources stories on Amazon's Mechanical Turk. "We instruct

Amazon's workers to describe a typical story about a given topic such as going

to a restaurant," he explains. Participants are sometimes given a character and,

using a specially created form, must fill in blank fields with snippets of story

(e.g. "Mary walked into the restaurant"; "Mary waited to be seated"; "Mary took

off her coat and ordered a drink").

The natural-language processing algorithms look for sentences from

different stories that are similar to each other and, from that information,

begin to draw conclusions about social rules and norms.

Algorithms to moral framework

An AI that reads 100 stories about stealing versus not stealing can examine

the consequences of these stories, understand the rules and outcomes, and begin

to formulate a moral framework based on the wisdom of crowds (albeit crowds of

authors and screenwriters).

"We have these implicit rules that are hard to write down, but the

protagonists of books, TV and movies exemplify the values of reality. You start

with simple stories and then progress to young-adult stories. In each of these

situations you see more and more complex moral situations," Riedl says.

Though it differs conceptually from GoodAI's, Riedl's approach falls into

the discipline of machine learning. "Think about this as pattern matching, which

is what a lot of machine learning is," he says. "The idea is that we ask the AI

to look at a thousand different protagonists who are each experiencing the same

general class of dilemma. Then the machine can average out the responses, and

formulate values that match what the majority of people would say is the

'correct' way to act."

There's a certain poetic symmetry to the solution: from the Golem to

Frankenstein's monster and beyond, humans have always turned to stories when

imagining the monstrous impact of their creations. Just as there are gloomy

conclusions to these stories, there is also a worry that, if you feed the AI

only dark plot lines, you could end up training it to be evil.

A woman holds the hand of the InMoov robot. Cautionary tale about the risks

of building a mechanical servant in man's image has gained fresh resonance in

the age of artificial intelligence. Vadim Ghirda

"The only way to corrupt the AI would be to limit the stories in which

typical behaviour happens somehow," says Riedl. "I could cherry-pick stories of

anti-heroes or ones in which bad guys all win all the time. But if the agent is

forced to read all stories, it becomes very, very hard for any one individual to

corrupt the AI."

The approach seems to be proving remarkably effective. "We know that the

system is learning from the stories in two ways," says Riedl. "First, we ran an

evaluation and asked people to judge the rules that the system learnt. Rules are

things like 'when going to a restaurant, ordering drinks comes before ordering

food'. Second, the system can generate stories, and these stories can be judged

by humans."

Common sense and surprises

For the most part, the team has found that the knowledge learnt by the

system is typically common sense. But there have been a few surprises. "When we

trained our system about going on dates to movie theatres, the system learnt

that 'kissing' was an important part of the schema. We weren't expecting that,

but in retrospect it's not surprising."

To the engineers at Audi building self-driving cars, or the technicians at

BAE Systems building autonomous weapons, teaching AIs when it is socially

appropriate to kiss or to queue might not seem directly relevant to their work.

But most advances in the fields of genetics, nanotechnology and

neuropharmacology may not, when considered in isolation, appear to have a moral

dimension, let alone a social one. Yet when the resulting technologies commingle

and are administered by AIs, the danger is that we discover that our

technological progress has outpaced our moral preparedness.

Riedl claims that we are at a crucial moment in history and, as a society,

we are faced with a simple choice. "We can say we can never have a perfect

robot, and because there's any sort of danger we should never do anything," he

says. "Or we can say: 'Let's do our best and try to mitigate the result.' We're

never going to have a perfect self-driving car. It's going to have accidents.

But it's going to have fewer accidents than a human. So … our goal should be to

be no worse than humans. Just maybe, it could be possible to be better than

humans."

In science fiction, the moment at which a robot gains sentience is

typically the moment at which we believe that we have ethical obligations

towards our creations. An iPhone or a laptop may be inscrutably complex compared

with a hammer or a spade, but each object belongs to the same category: tools.

And yet, as robots begin to gain the semblance of emotions, as they begin to

behave like human beings, and learn and adopt our cultural and social values,

perhaps the old stories need revisiting.

At the very least, we have a moral obligation to figure out what to teach

our machines about the best way in which to live in the world. Once we've done

that, we may well feel compelled to reconsider how we treat them.